At 9:30 am on March 12, 1963, in Room 1-B of Manhattan’s Rockefeller Institute, six experts gathered to discuss the implications of a newly identified atmospheric phenomenon: the rising level of carbon dioxide (CO2) caused by the burning of fossil fuels.

Hosted by the Conservation Foundation, a philanthropic organization, this small but vitally important symposium would help to bring a practically unknown area of scientific inquiry to national awareness.

“Man is altering the balance of a relatively stable system by his pollution of the atmosphere with smoke, fumes and particles from . . . fossil fuels” and by “the increasing quantities of carbon dioxide an industrial society releases to the atmosphere” wrote the foundation’s president, Samuel H. Ordway, Jr., in the foreword to the group’s 1962 Annual Report. Concerned by potential climatic consequences, the foundation had proposed a conference on the “Carbon Dioxide Content of the Atmosphere” — an informal symposium that would allow a selected panel of experts to clarify their thinking and crystallize their ideas for “future scientific research” on the topic.

By sounding the alarm over CO2-induced climate change, and attempting to propel the issue out of the lab and into the limelight, this long-overlooked conference essentially inaugurated what would become the global climate action movement. Almost a half century before Al Gore’s seminal film and book, “An Inconvenient Truth,” the conference organizers produced what appears to be the first publication devoted entirely to the subject of CO2 and climate change. They distributed 700 free copies of the document to raise awareness of the issue and stimulate planning for the prevention of future catastrophe.

These never-before-seen documents recently discovered as part of DeSmog and Climate Investigation Center’s ongoing exploration of early public awareness of climate science, were found at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center; the Charles David Keeling Papers at the University of California, San Diego; the U.S. National Archives; and the LBJ Presidential Library. They reveal that within a year of the conference the issue of CO2-caused climate change would be brought to the attention of policy makers inside the U.S. Government.

Early Example of Corporate Greenwashing

The location chosen for the conference was New York’s Rockefeller Institute established in 1901 by John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil (now ExxonMobil). The Rockefeller Foundation, which maintained a close association with the Rockefeller Institute, was a prominent sponsor of the Conservation Foundation, as was the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, giving a combined total of $35,000 (worth almost $350,000 today) to the conservation group in 1962, the year in which the conference was organized.

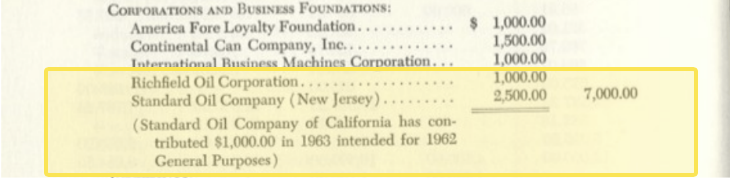

According to the Conservation Foundation’s “Summary of Receipts” for that year, Laurance S. Rockefeller (the financier, philanthropist, and conservationist who was a grandson of John D. Rockefeller) made substantial donations. Three major oil companies also contributed smaller amounts — $2,500 from Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil); $1,000 from Standard Oil of California (Chevron); and $1,000 from the Richfield Oil Corporation (BP).

A newly discovered internal document authored by Standard Oil of New Jersey (ExxonMobil) in 1966 suggests that its donation was made for PR purposes in an early example of corporate greenwashing. The document, found in the ExxonMobil Historical Collection in Austin, Texas, reveals that one of the company’s PR objectives “as approved by the Board in 1962” was “to work for a climate of opinion at home and abroad that will encourage fair opportunity for its operations.”

Team CO2

The Conservation Foundation invited a handful of experts, mostly scientists interested in the Earth’s natural systems, to participate in the conference. Like the foundation itself, some of these scientists also had connections to the fossil fuel industry, highlighting the close relationship between the industry and climate science during this time.

First on the list was Edward Deevey, a Yale ecologist and paleontologist, who, funded by another Rockefeller Foundation grant, had used carbon dating to develop a global climate history.

Second was Erik Eriksson of the Swedish International Meteorological Institute, whose 1958 paper, “Changes in the Carbon Dioxide Content of the Atmosphere and Sea Due to Fossil Fuel Combustion,” demonstrated how fossil fuels were contributing CO2 pollution to the atmosphere.

Next up was Charles D. Keeling a geochemist from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, whose measurements of atmospheric CO2 from the Mauna Loa Observatory revealed steadily rising levels of the gas that would come to be depicted in the iconic “Keeling Curve.” According to newly discovered documents, Keeling’s earliest CO2 research, measuring concentrations across the western United States in the mid 1950s, was funded by the Southern California Air Pollution Foundation. This foundation was formed to tackle the Los Angeles “smog problem,” and was sponsored by automobile manufacturers and oil producers.

Curious about Keeling’s early CO2 research? Read Part 1 of this investigation.

After Keeling came Gilbert N. Plass from the Ford Motor Company. A former physics professor at Johns Hopkins University, Plass had published articles on carbon dioxide and climate in scientific journals, including American Scientist, Tellus, and the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. These articles contained evidence that burning fossil fuels was responsible for a documented rise in global temperatures over the 20th Century.

Finally, Lionel Walford of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Atlantic Marine Laboratory, an expert on the impact of human activities on fish, joined the panel, along with William A. Garnett, a pioneer in aerial photography who had documented the effects of expanding human activities on the U.S. landscape.

The evening before the symposium, a cocktail reception was held for the participants at the apartment of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Ordway, Jr., in Manhattan, not far from the Rockefeller Institute. The next morning, however, it was down to business with lunch provided and a stenographer present to record the discussions “for subsequent analysis.”

CO2 Will Have Serious Consequences

The product of the symposium was a farsighted, slim publication, “Implications of Rising Carbon Dioxide Content of the Atmosphere,” which contained a fateful synthesis of the views expressed by the conference’s participants.

“It is known that the carbon dioxide situation, as it has been observed within the last century, is one which might have considerable biological, geographical and economic consequences within the not too distant future,” the foreword stated. “What is important is that with the rise of carbon dioxide, by way of exhaust gases from engines and other sources, there is a rise in the temperature of the atmosphere and oceans.”

The authors hoped the publication would contribute to further examination of “the carbon dioxide situation,” which was described in the foreword as a subject of “considerable concern and controversy.”

Although the report acknowledged the uncertainties surrounding the emerging science of carbon dioxide and climate change, it also noted that these uncertainties were in themselves a cause for concern. “The most alarming thing about the increase of CO2 is how little is actually known about it,” the report declared, before warning that very little consideration had been given to “man’s manipulation of the environment.” While “the checks and balances are numerous, there are not enough data to evaluate them with certainty,” it continued. “The present liberation of such large amounts of fossil carbon in such a short time is unique in the history of the earth,” the report stated, “and there is no guarantee that past buffering mechanisms are really adequate.”

This rise in atmospheric CO2 was “worldwide,” the summary reported, and, while it did not present an immediate threat, would be significant “to the generations to follow.” The document went on to say, “The consumption of fossil fuels has increased to such a pitch within the last half century, that the total atmospheric consequences are matters of concern for the planet as a whole.” Relief was likely “only through the development of some new source of power.”

Want to be the first to know about investigations like this? Sign up for our newsletter!

Moreover, foreshadowing events 50 years on, a consensus view prevailed among the authors that the continuing rise in the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide was likely to be accompanied by a “significant warming of the surface of the earth, which by melting the polar ice caps would raise sea level.”

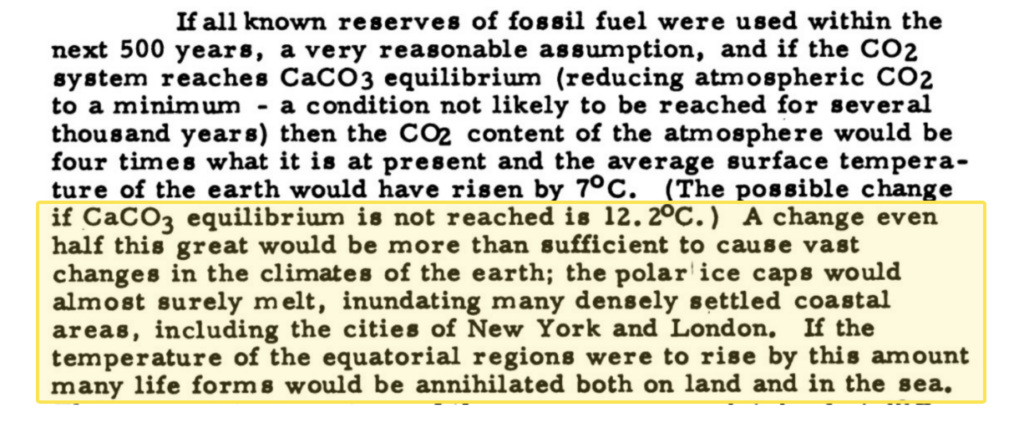

If all known reserves of fossil fuels were used within the next 500 years, the report predicted that “the CO2 content of the atmosphere would be four times what it is at present and the average surface temperature of the earth would have risen by 7 degrees Centigrade.”

However, envisioning the climate scenario we are heading toward today, the report argued that “a change even half this great would be more than sufficient to cause vast changes in the climates of the earth; the polar ice caps would almost surely melt, inundating many densely settled coastal areas, including the cities of New York and London. If the temperature of the equatorial regions were to rise by this amount many life forms would be annihilated both on land and in the sea.”

The participants agreed that more structured research was needed and the lack of overall information was cited as a problem. However, in a statement that foreshadowed the impacts of climate denial in the decades to come, they noted that a more serious problem was that of “convincing people that there is a problem at all.”

In conclusion, the report underscored that it was “very important to alert more people, more scientists and more scholars in the social sciences as well as the pragmatical sciences, to the need for planning, and the realization that there is an obligation to provide for the future as well as the present.”

With this goal in mind, Ordway wrote to Keeling in September 1963, informing him that a summary of the transcript of the CO2 symposium was available for distribution. According to Ordway’s letter, 700 copies would be mailed to “persons selected” from the foundation’s regular mailing list and “a few others” who “might be particularly interested.”

A list of these 700 selected recipients has not yet been located. However, it is likely that all the Conservation Foundation’s contributors and benefactors — including its corporate sponsors Standard Oil of New Jersey, Standard Oil of California, and Richfield Oil — received a copy of the publication with its extensive discussion of “the carbon dioxide situation” and its declaration that “as long as we continue to rely heavily on fossil fuels for our increasing power needs, atmospheric CO2 will continue to rise and the earth will be changed, probably for the worse.”

It is not yet known if executives from these three oil companies read the Conservation Foundation’s “Implications of Rising Carbon Dioxide Content of the Atmosphere” or its 1962 Annual Report. But if they did, this information regarding CO2 and climate change would not have been entirely new to them. As historian Benjamin Franta has shown, three years earlier, in 1959, at an event organized by the American Petroleum Institute to commemorate the oil industry’s 100th birthday, physicist Edward Teller warned oilmen that CO2 from burning fossil fuels caused “a greenhouse effect,” which, if left unchecked, would result in a global temperature increase that was likely to melt the earth’s ice caps and raise sea levels.

Corridors of Power

By May of 1964, records show that at least one of the 700 copies of the Conservation Foundation’s report made its way to the Air Pollution Division of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW), which, prior to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, was responsible for matters related to national air pollution.

HEW produced a draft report that same month outlining “National Objectives for Atmospheric Science Research” which contained a section summarizing the effects of air pollution on “Weather and Climate.”

The draft report stated that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere was increasing “as a consequence of human activities,” emphasizing that this increase was raising the temperature of the earth’s atmosphere, and would lead to “more violent air circulation and thus to more destructive storms.”

Citing the “recent report by the Conservation Foundation,” HEW’s draft showed that fuel combustion by all industrialized nations was currently adding about 1.6 parts per million of CO2 to the atmosphere each year. Anticipating warnings from climate scientists and activists today, the draft goes on to state, “If this continues unabated, it threatens in the not too distant future (as history measures time) to increase the average surface temperature of the earth by as much as 7 degrees Centigrade.”

“A change even half this great would be more than sufficient to cause vast changes in the climate of the earth,” according to HEW’s summary, lifting sections of the text from the Conservation Foundation’s report verbatim. The prescient summary went on to say, “The polar ice caps would almost surely melt, inundating many densely settled coastal areas … and many life forms would be annihilated both on land and in the sea. Air pollution’s effects on the weather, therefore, can be significant on a large scale as well as locally.”

Although the reference to “more destructive storms” was removed from the final version of the report, the minutes of a HEW meeting in June 1964 record discussions that the next draft should “expand and revise discussion of CO2.”

When did a U.S. President first learn about the link between CO2 and climate change? Read Part 3 to find out.

These documents show that by May 1964, earlier than previously documented by climate historians, members of the federal government department responsible for air pollution were aware of the latest developments in the science of carbon-dioxide-induced climate change and were actively working to make further investigations a national priority.

The final HEW report, dated October 16, 1964, echoed the Conservation Foundation report’s key conclusions, stating that the potential effects of pollution on the heat balance of the earth posed “a serious question.” Levels of CO2 in the atmosphere responsible for the “greenhouse” effect were steadily increasing, while “only about half the CO2” produced by the combustion of fossil fuels were being removed from the atmosphere by natural processes, the agency stated. The final report also referred to the suggestion that increased atmospheric CO2 was causing a parallel increase in average air temperatures, particularly in northern latitudes. It emphasized that, because small changes in average temperatures could make a dramatic impact on the polar ice caps, the significance of potential climatic influences was “far greater than our existing knowledge of these influences.”

Despite this fact, HEW’s report optimistically concluded that “the same scientific and technological know-how which created the wonders of modern living” would also probably develop a way of controlling the unwanted by-products of air pollution. An all-important proviso was added: The air pollution problem was likely to be solved, argued HEW, “once everybody concerned is fully aware of the need.” However, fossil fuel industry campaigns against climate science in subsequent decades obstructed this potential solution.

The following year, in 1965, the Conservation Foundation’s report — along with the individual work of Eriksson, Keeling, Plass, and other renowned climate scientists such as Roger Revelle — would provide key evidence for a landmark report on environmental pollution by the President’s Science Advisory Committee, bringing the “carbon dioxide situation” one step closer to the heart of government.