The literature search produced 6961 results. De-duplication removed 2206 results and the titles of the remaining 4705 results were screened resulting in the removal of a further 4230 studies. Following this, 475 results underwent further screening, with 36 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. An additional nine results were identified through systematic review bibliography screening, and 73 during grey literature searches, of which five results met the inclusion criteria, giving a total of 41 studies (30 unique interventions) to be included (Supplementary Material 3.).

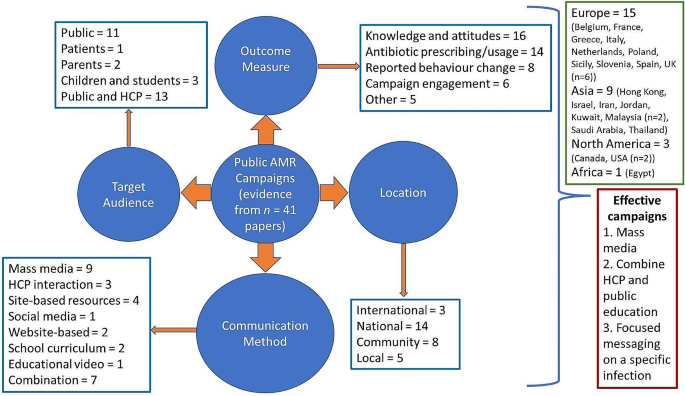

Table 2. provides an overall summary of the studies included within this review and Table 3. Outlines the key focus of the included campaigns. The search showed a range of countries, both high and middle income, within which AMR campaigns or interventions had been conducted. However, most campaigns were conducted in high income countries (n = 23) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], with six campaigns conducted or originally developed within the UK [35, 39,40,41,42,43], and four [44,45,46,47] and two [48, 49] campaigns conducted in upper and lower middle-income countries respectively. A summary of the campaign characteristics is available in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of campaigns included within the review

Study design

The majority of studies used cross-sectional [18, 21, 27, 29, 30, 34, 35, 37, 40, 42, 45, 47, 50,51,52,53] or longitudinal study designs [19, 20, 22, 24, 38, 39, 44, 46, 53, 54], (n = 14 and 10 respectively). five used a quasi-experimental [25, 32, 33, 36, 49] and two used an experimental design [23, 56].

Target population

The primary focus of 17 of the campaigns was the public [19, 21, 23, 24, 30, 33, 35, 38, 46, 49, 55], with two school curriculum-based campaigns focused on children [26, 27, 42, 47], two further campaigns focused on parental education [20, 44], and one campaign focused on patients [56]. The remaining 12 campaigns targeted both HCP and the public [18, 22, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 36, 45, 48, 57, 58].

Campaign type and communication methods predominantly used

Most were national campaigns (n = 13) which used mass media to disseminate information (n = 7) [19, 21, 22, 24, 38, 39, 45]. Other national campaigns used the school curriculum [47], social media [31], websites [29, 37], and interactions with HCP combined with education resources [28, 36] to communicate with their target audiences. Eight studies evaluated community or regional-level campaigns, with site-based resources, such as poster displays and leaflets, the most common communication method (n = 5) [20, 25, 32, 48, 49]. Local campaigns used HCP interaction (n = 2) [46, 56] and site-based resources, such as posters (n = 3) [30, 35, 40]. Finally, three international campaigns were identified which used mass media [58], school curriculums [26, 27, 42], and website content [37] to disseminate information.

Outcome measures

Change in participants knowledge of and/or attitudes towards AMR was predominantly used as an outcome measure (n = 16) [22, 23, 30, 33, 34, 38, 39, 43, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 55, 59]. Trends or changes in antibiotic prescribing or usage was also commonly used (n = 14) [18, 19, 21, 23–24, 32, 36, 48, 52,53,54,55, 60]. Other outcome measures used included reported behaviour change (n = 8) [23, 37,38,39, 49, 51, 56, 57], campaign engagement (n = 6) [29, 31, 50, 51, 57, 61], expenditure on antibiotics (n = 2) [19, 21], annual number of GP consultations (n = 1) [21], severity of respiratory tract infection symptoms (n = 1) [35], and perception of campaign messaging (n = 1) [62].

Changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour

Table 4. summarises studies which assessed changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviour following the campaign. Studies reviewing the pledge-based Antibiotic Guardian campaign assessed self-reported change in knowledge which shows 44·5% of Antibiotic Guardians reported an increase in knowledge post-campaign. This was more likely in individuals with limited pre-campaign knowledge of AMR (OR: 4·21, CI: 2·04–8·67) [37]. Furthermore, when making a pledge, Antibiotic Guardians were asked five knowledge-based questions. Comparison of these to Eurobarometer questionnaire responses by the UK or EU public showed Antibiotic Guardians answered more questions correctly (OR: 8·5 and 13·9 respectively) [51, 63]. However, not all studies analysing the Antibiotic Guardian campaign reported positive findings only. A qualitative analysis by Kesten et al. showed that a limited number of Antibiotic Guardians could fully recall their pledge and reports regarding improved knowledge following participation in the campaign were mixed [57].

Multiple campaigns used a pre- and post-campaign comparison of a knowledge-based questionnaire to determine the campaign’s effectiveness. Ho et al. showed a significant increase in knowledge regarding the ineffectiveness of antibiotics at treating viral infections following a mass media campaign promoting the key message “Antibiotics do not help in cold and flu” [22]. Thong et al. and Shehadeh et al. assessed the effect of one-to-one educational sessions conducted by HCPs; both showed significant improvements in knowledge of antibiotic use and resistance [44, 46]. Another intervention using a taught component delivered education sessions to school children as part of the school curriculum in Malaysia [47]. Assessment of knowledge showed a significant improvement in both mean knowledge and attitude scores as well as a correlation between the two scores. Finally, using independent samples, Mazinska et al. evaluated the impact of European Antibiotic Awareness Day (EAAD) in Poland [34]. Questionnaire data was collected from a random sample of adults aged over 18-years pre and post EAAD in 2009, 2010 and 2011 and showed those who were aware of the EAAD campaign (29·0% of respondents) had significantly better knowledge of appropriate antibiotic usage than those who were not aware of the campaign, especially regarding the use of antibiotics to treat RTIs [34].

A British public antibiotic campaign launched in 2008 was also evaluated using pre- and post-campaign questionnaire data [39]. While recognition of campaign materials, such as posters, increased over the campaign period, there was no significant change in attitudes, including attitudes towards the use of antibiotics to treat colds and flu despite this being the campaign’s key message. Furthermore, no significant change in self-reported antibiotic use occurred following the campaign. However, the latter Keep Antibiotics Working campaign showed significant improvements in some aspects of public knowledge [43]. Campaign recognition was higher than for the 2008 campaign (23·7 vs. 71·0%) and knowledge increased significantly for AMR specific questions such as “antibiotics will stop working if taken for the wrong things”. Levels of concern about AMR within the public also increased significantly post-campaign.

Changes in antibiotic prescribing

Table 5. summarises findings from studies which used antibiotic prescribing rates as their primary outcome measure. Studies that determined the effectiveness of the 2002 French mass media campaign used antibiotic prescribing data, obtained from several sources including prescribing panels, sales data from IMS Health France, government organisations, and National Insurance reimbursement data, as a primary outcome measure [21, 52,53,54]. These studies indicated a significant reduction in antibiotic prescribing with reductions of up to 33·0% during the final campaign period from 2009 to 2010. This effect however was not consistent across age groups with greater reductions seen in children compared to older adults, which is thought to be due to the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate (7-valent) vaccine for children aged less than 5-years old [54]. Furthermore, Dunais et al. also analysed a local intervention which commenced in 2001 and ran alongside the national campaign until 2003 [18]. This local intervention was focused on GPs and paediatricians and aimed to improve the management of RTIs in children under the age of 6-years. Analysis of antibiotic prescribing data obtained from children’s health books showed a 50·0% reduction in the number of children receiving antibiotic prescriptions between 1999 and 2008. This reduction occurred despite no significant change in the average weekly number of RTI and bronchiolitis cases reported by GPs. Dommergues & Hentgen also found a 50·4% reduction in national annual antibiotic prescriptions within children aged under 18-years from 2001 to 2010, with the greatest reduction seen in children aged 0 to 24 months (57·2%) [21]. Although antibiotic prescribing rates have stabilised in recent years, Carlet et al. observed antibiotic prescribing rates remained 12·6% below baseline levels 14-years post-campaign [53].

The Belgium mass media campaign also used antibiotic prescribing data (defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID)) to show a significant impact from the campaign [19]. Following an initial decline of 12·1% from baseline to the end of the second campaign wave in 2007, prescribing rates fluctuated. However, the reduction in prescribing was maintained at 12·6% in 2018.

A pilot campaign in Egypt which aimed to raise awareness of rational antibiotic prescribing for RTIs among physicians, pharmacists, and the public used training courses to educate HCPs and social media to disseminate information within younger populations [48]. A 25·0 and 22·0% decline in antibiotic prescribing was seen post-intervention for children and adults respectively, with changes mainly being driven by reductions in prescribing for ear infections and bronchitis.

Studies evaluating the Canadian “Do Bugs Need Drugs” campaign reported inconsistent effects on antibiotic prescribing. Cumulative observed antibiotic use during the three years following the campaign implementation was 5·8% lower than expected values, with greater effects seen in the number of prescriptions dispensed to children (-10·6%) [23]. Furthermore, the effect on prescribing rates was dependent on the type of antibiotic and the condition for which the antibiotic was being prescribed [55].

Studies by Formoso et al. and Plachouras et al. used similar quasi-experimental study designs with campaigns implemented in specific regions with neighbouring provinces and national rates used as controls [23, 32]. Formoso et al. focused on antibiotic use in RTIs and used social marketing strategies to develop campaign messaging. Messaging was then disseminated via local media channels. Analysis of regional outpatient prescribing databases showed a significant 4.3% (95% CI: -7.1 to -1.5%) reduction in prescribing (DID) in intervention compared to control areas. Plachouras et al. relied on two-hourly education sessions for parents conducted by local HCPs and had limited use of the media to promote information. Within the Greek test regions antibiotic consumption was unchanged following the intervention and continued to follow trends seen nationally and within control regions.

A Slovenian campaign predominately aimed at HCP through educational workshops and the implementation of prescribing guidelines and restrictions, but with an element of public education in the form of flyers and posters on topics such as “The safe use of drugs” and “Get well without antibiotics” was implemented in 1995 [36]. Following an initial increase in prescribing rates of 3·97 DID from 1995 to 1999, antibiotic prescribing decreased resulting in a small net decrease of 5·0% since the campaign’s initiation.

Finally, a community campaign in 2018 which enrolled 21 clinics across ten locations in the USA also targeted HCPs through educational sessions and a cross-clinic comparison of prescribing data, with educational materials also provided to patients [25]. Assessment of the number of antibiotic prescriptions written for unresponsive RTIs showed a 46·0% reduction in prescribing post-intervention (OR: 0·54, 95% CI: 0·42 − 0·66, p = 0·001) after controlling for seasonality. However, this level of effect only occurred in two of the eleven clinics included in the study and no significant long-term intervention effect was evident.

Overall, a pooled analysis of the effect of European campaigns on DID’s suggest that implementation of a public campaign may reduce antibiotic consumption by 1·3 to 5·6 DID per 1,000 inhabitants [60].

Other outcome measures

Some campaign and intervention evaluations used other outcome measures. For example, campaign recognition and engagement were used by multiple studies evaluating the Antibiotic Guardian campaign. 26·5% of unique visitors to the Antibiotic Guardian campaign website made a pledge, 10·1% more than for a similar pledge-based campaign conducted in Sicily [29], with social media creating the greatest number of unique visitors to the Antibiotic Guardian website (29·0%) [61].

Similarities between campaigns reported to be effective

Evaluation of fourteen campaigns saw a significant improvement in their primary outcome measure, however there was a lack of homogeneity between these campaigns. Targeting a specific infection type (e.g. respiratory tract infection) was a common theme among campaigns that saw significant improvement in their primary outcome measure, these campaigns (n = 10) focused messages on the ineffectiveness of antibiotics at treating RTIs. Key messaging included “Antibiotics are not Automatic” [18, 21, 52,53,54], “Antibiotics are ineffective for common cold, acute bronchitis and flu” [19], “Antibiotics do not help in cold and flu” [22], and “Do Bugs Need Drugs” [24].

Mass media was used to disseminate messages in seven campaigns. The use of TV advertising to promote campaign messages was a recurring feature in mass media campaigns which saw a significant improvement in their primary outcome measure and was often cited as the main source of campaign recognition [19, 34, 38, 55]. Finally, some of these mass media campaigns which were reported as being effective also included an element of HCP education or promotion of HCP-patient interaction. This ranged from feedback to GPs on their antibiotic prescribing based on reimbursement data and facilitation of discussions between HCP and patients [19] to academic detailing, individual prescribing feedback and promotion of rapid streptococcal antigen tests [52] to promotional materials sent to all medical doctors and pharmacists [22], and accredited educational courses for physicians and pharmacists [24, 55].

A common theme among local and community interventions that saw a significant improvement in their primary outcome measure was an element of HCP education and using HCP-patient interactions to disseminate information. Part of the intervention implemented by Maor et al. included an explanation by physicians to parents for the reason their child has not been prescribed antibiotics during their visit [20]. Furthermore, Shehadeh et al. employed a similar method of disseminating information by employing pharmacists to provide ten-minute education sessions to the public on a one-to-one basis [46]. Finally, Kandeel et al. and Morgan et al. implemented HCP training programmes focusing on appropriate prescribing for RTIs for all clinical specialties, primary care doctors, as well as pharmacists and physicians working within outpatient clinics respectively [25, 48]. These training programmes were supplemented by educational resources targeting both HCPs, patients, and the public. Finally, the two remaining campaigns used school curriculum and social media combined with site-based resources to share campaign messaging regarding AMR and antibiotic use.

Campaign duration varied from 4 months [46] to 19-years [19] and did not seem predictive of significant improvements in the campaign evaluations primary outcome measure with only mass media campaigns repeated annually.