Search results

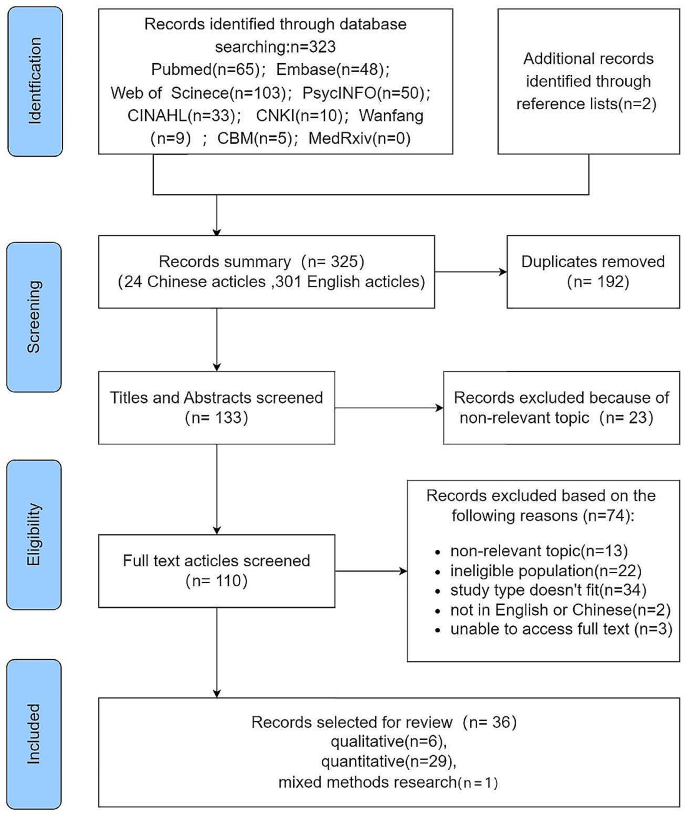

The primary search discovered 325 papers, including 24 Chinese and 301 English articles. After removing duplicates, 133 papers were left. We selected 110 articles for full-text reading based on screening titles and abstracts. We excluded 74 articles due to unrelated topics (n = 13), ineligible study populations (n = 22), noncompliant study designs (n = 34), not in English or Chinese (n = 2), and unobtainable full texts (n = 3). Finally, our analysis included 36 studies. Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the search strategy and the selection process based on identified criteria.

Flow diagram of screening of articles based on identified criteria

Characteristics of sources of evidence

Five of the 36 articles were in Chinese, with the remaining 31 in English. Three were published in 2020, 15 in 2021, and 18 in 2022 (one of the studies was online in 2022 and published in 2023). The study included18 articles from China, four from Turkey, three from the United States, three from Korea, one from other countries, such as Greece, Italy, Canada, Spain, Israel, Serbia, and Palestine, and one from a global study covering three countries (Israel, Canada, and France).

The study population included 17 papers on frontline medical staff (care for COVID-19-diagnosed patients), four papers on nurses diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, and 15 on medical workers. It involves the emergency department, intensive care unit, dentistry, psychiatric department, and outpatient department. The medical institutions involved hospitals designated to treat patients diagnosed with COVID-19, general hospitals, communities, clinics, and other hospitals. The PTG level was measured at one to three-time points in 23 cross-sectional and six longitudinal studies, primarily using online questionnaires. Six qualitative articles utilized semi-structured interviews and questionnaires via telephone, video, or face-to-face interviews. Scale and open-question surveys were used in one mixed mothed record. Table 1 represents the general characteristics of the included literature.

Synthesis of results

Quantitative results

The level of posttraumatic growth

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), a 21-item scale developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun [2] in 1996, measures PTG, including five dimensions: relationship with others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life. It is scored on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 to 5, ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Researchers in various regions have modified this scale based on cultural adaptation. Most Chinese studies used the revised version of the 20-item PTGI by Wang Ji [58], deleting item 18, “My religious beliefs are stronger,” due to its low correlation with the total score and local culture in China. It adopted the Likert 6-point scale with a score of 0–100. Six studies [28, 32, 36, 37, 43, 44] used a 10-entry short version of the PTGI scale (PTGI-SF), adopting a Likert 6-point scale with a total score of 0 to 50 [59]. Tedeschi et al. [60] updated the list with four new items in the spiritual and existential change subscale to better capture spiritual and existential change in non-religious cultures, comprising PTGI-X with 25 items scored from 0 to 125 with a 6-point Likert scale. Two studies included in this review used it as a measurement [25, 55]. PTG levels reached moderate and above with mean item scores of PTGI > 3 or total scores > 60 in two studies [24, 38]. However, another study indicates that people who scored higher than the 60th percentile might have grown [37].

HCWs experienced varying PTG levels following direct or indirect trauma during the COVID-19 epidemic. A total of 28 studies in the included literature reported specific PTGI scores, with moderate PTG levels in general and high scores on the dimension of “relating to others”, “appreciation of life”, and “personal strength” more frequently mentioned. Table 2 presents the details.

The influencing factors of posttraumatic growth

Trauma

COVID-19 could be categorized as a new type of mass trauma. Different types of trauma-related scenarios or characteristics may influence PTG levels. COVID-19-exposed HCWs, such as those working in intensive care units (ICUs) or frontline or sentinel hospitals where confirmed cases are treated, had higher PTG levels [23, 29, 37, 45, 51]. HCWs diagnosed with COVID-19 or have a family member, friend, or colleague who has been diagnosed had higher PTG levels [51, 56].

The PTG levels of HCWs differed at different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal study of frontline HCWs (n = 134) in China showed that Time 1 (Feb 2020) to Time 2 (Mar 2020) participants revealed an increase in PTG, while Time 3 (May 2020) participants indicated a decrease in PTG [42]. Another three-wave longitudinal study (n = 565) from China discovered that PTG gradually increased over two years of follow-up among HCWs, and four types of PTG trajectory were identified: persistent, steady increase, high with a drop, and fluid trajectory [22]. However, one study (two-point survey) from Turkey indicated that PTGI scores decreased significantly over time among 66 HCWs participated in the study [24]. Another two-wave survey from the U.S. radiology staff revealed a consistent trend toward lower PTGI [23].

The severity of the traumatic event and PTG in HCWs may have a positive or negative correlation. Researchers have also discovered that PTG was negatively correlated with trauma [28] and PTSD symptoms [47]. Another study indicated that PTG was positively correlated with PTSD [36].

Demographic characteristics

Gender, age, work years, job title, education level, marital status, child status, religion, and race may be associated with PTG. Most studies discovered higher PTG levels among HCWs with older age [22, 23], longer working years [33, 38], higher job titles [51], and higher education levels [22, 51]. However, some studies revealed that PTG was negatively correlated with age [25, 34] and professional title [47]. Not coincidentally, gender differences were also observed across studies. A survey of 455 nurses from China indicated that women had lower PTGI scores than men [29]. A survey of 673 HCWs from Greece showed that women scored higher on all VPTG subscales [34]. However, another large (n = 12,596) study from China demonstrated a greater trauma response in women than in men but no difference in PTG [37]. Similarly, a study from Serbia produced consistent results [56].

Additionally, HCWs with religious beliefs [32, 33], married [29], with children [39], and working part-time [32] had higher PTG levels. PTG levels differed between physicians and nurse assistants [43], and whether they were white [36] or born locally also differed from PTG levels [33]. Disaster training, rescue, critical patient resuscitation, and infectious disease treatment experience contribute to a higher PTG level [51].

Psychological factors or personal traits

Positive emotions or psychology or personal traits can promote PTG, such as resilience [22, 26, 33, 42], occupational resilience [50], occupational identity [45], self-efficacy [47], deliberate rumination [30, 38, 55], subjective well-being [28], coherence [28], harmonious passion [43], frontline job confidence [38], risk awareness [38], transformative power of pain [31], trust, reciprocity, and identification [41], being psychological comfort [39], and positive emotions and dispositional gratitude [36], as mentioned in most studies.

Negative emotions or psychological or personal traits can inhibit the PTG onset; examples include COVID-19-related stress/anxiety/concern [28] and job burnout [28, 42]. However, similar to trauma, the stress/anxiety/concern associated with COVID-19 has also revealed a double-edged sword effect on PTG. For instance, research from China exhibited that higher COVID-19-related worries and psychological distress meant a higher PTG level [32]. Studies from other regions have demonstrated the same effect [43, 44]. An increased stress mindset, determining the stress response, is associated with higher PTG levels [25].

Coping and social support

A positive coping style can contribute to PTG, including conducting psychological interventions/training, engaging in online counseling, and phone app of application self-relaxation [25, 29, 38, 47, 56].

A positive association has been demonstrated between PTG and social support, including support from organizations [26, 50], societies [30, 45, 47, 53], families [39, 52], and friends [39]. Additionally, good working relationships, such as nurse-patient satisfaction [51] and job satisfaction [32], can promote PTG in HCWs.

Seven studies explored the path analysis of the PTG influencing factors and discovered the mediating and moderating factors under their respective theoretical models, such as organizational support [50], social support [30, 57], coping strategies [25, 34], resilience [53], psychological security [41], expressive suppression [53], deliberate rumination [30], emotional exhaustion [42], self-disclosure [30], and positive psychological capital [57].

Qualitative results

Six qualitative studies [27, 35, 40, 46, 48, 54] described the specific experiences of HCWs when confronted with or diagnosed with COVID-19 through three periods of stress/negativity, adjustment to adaptation, and growth, presenting PTG occurrence. The qualitative part of another mixed study [49] identified three themes: quality of workplace relationships, sense of emotional-relational competence, and clinical-technical competence. Each theme has two broad macro categories: growth and block.

Change in relationships with others

Six of the Seven studies contributed to this theme. Improved interpersonal relationships include with family, friends, colleagues, and patients. Family, friends, and colleagues’ warm love and support bring their relationship closer and more intimate. A nurse diagnosed with COVID-19 remarked, “My boyfriend cared for me, encouraged me, and gave me strength after I got sick; I will cherish the relationship between us” [54]. “When I saw my son at the gate of the community after I came back from isolation, I burst into tears and held him tightly in my arms” [27]. As healthcare worker spends more time with a patient, their empathy and compassion for the patient gradually intensifies. Like comrades who fought back the “enemy” (COVID-19), both sides cheered and encouraged each other to overcome difficulties and diseases, improving the relationship between doctors and patients. One nurse said, “When the test result returned negative for the first time after being admitted, I was so happy and cried together with the patients” [48]. Additionally, the experience of being a patient after a COVID-19 diagnosis also influences how HCWs treat patients, and role reversal and empathy improve the relationship with patients to some extent [27, 54]. During this particular time, colleagues’ help, care, and encouragement in caring for infected patients promote teamwork and interpersonal relationships [27, 35, 48, 49, 54].

Increase in individual strength

This resulted in a shift in participants’ mental and professional perceptions of themselves. At a psychological level, HCWs reported that the experience had made them more courageous, strong, and optimistic. “I think I am a little more brave and strong than I thought I would be” [54]. In the face of difficulties or trauma, resilience allows individuals to make positive choices and respond rationally to stress. This facilitates guiding individuals to reconstruct non-adaptive states and activate their potential to resist crises to resolve difficulties. Most HCWs described their experiences exploring and reconfiguring their strengths [27].

At the professional level, HCWs had a positive attitude toward gaining work experience related to a new infectious disease [48, 49]. They viewed their current experience as a valuable opportunity to learn new skills and enhance their work, gradually moving from unfamiliarity at the beginning to completing the work previously given to the nurse aides and being able to quickly shift and focus on enhancing the quality of care and improving patient well-being. This adds significance to their experience [48].

Changes in the philosophy of life and priorities

Four of the seven studies contributed to this theme. Interviewees mentioned a new appreciation of life and the future after experiencing trauma. They will re-examine life’s meaning and re-plan their future priorities, such as“I felt the need to live more meaningfully as the disease gave me another chance to live. I became more attached to life and realized how valuable it is …” [40].

Most life priorities change are reflected in the increased priority given to physical health. “Nothing is better than a healthy life, and nothing is as important as health” [27]. “… I realized that health is more important than anything else. Thus, I decided to stop worrying about some things, stop overthinking, and stop to give importance. I realized that health is the most important thing” [40]. Moreover, it is reflected in other meaningful and fun things, such as “I will get better for myself and my family. I will spend more time with them, cherish every day, and enjoy the fun of life. I still have many important tasks to complete” [27].

Self-identification of profession

Participants in four studies described greater vocational identity. Most participants expressed satisfaction and pride that they were making a concrete contribution to the fight against the global pandemic. Their pride was further enhanced with increased social recognition of HCWs caring for COVID-19 patients. All of these enhanced their professional identity. “The work that I am doing is truly helping others. I am contributing during this national disaster situation. I am here at this historical moment…” [48], “I am proud to be a nurse and to have assisted on the front lines” [35], and “I think every HCW is a hero” [54]. As child and adolescent psychiatrists, they have experienced a successful transition from “who we are” and “what we can do now” to “who we will become” during the pandemic and then engendered a reevaluation of and a recommitment to psychiatry [46].

Spiritual change

One research reported a change in spirituality [40]. After being diagnosed with COVID-19, the nurses questioned their spiritual lives and changed. “Inevitably, death anxiety enters your mind, and you question yourself. I realized how spiritually weak I was and made a promise to myself. I would pay more attention to my prayers after the treatment … I was angry with myself as I was living in this way….” “Thus, I realized that everything was in vain; the only real thing is after death. … I started to question my mistakes and sins and plan to get rid of them … I turned to God more.” Many of them rely on religious beliefs to manage stress.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative research

To provide a clearer understanding of the consistency and divergence between quantitative and qualitative studies in the PTG of HCWs, we have established Table 3 to compare the associations of these two research methods regarding PTG characteristics and influencing factors.

Through the comparison presented in the table, we observe a notable coherence and complementarity in understanding the characteristics and influencing factors of PTG among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In terms of PTG characteristics, the themes distilled from qualitative studies correspond closely with the five dimensions measured in quantitative PTG scales. This alignment elucidates the specific contexts and manifestations of these dimensions, providing a clearer and more comprehensive understanding of what PTG looks like for HCWs in the context of the pandemic. Regarding influencing factors, there is a synergistic relationship between the themes identified in qualitative research and the factors statistically derived from quantitative studies. For instance, qualitative themes such as “Work-related stressors” and “Psychological stress and emotional reactions” offer a vivid explanation of HCWs’ early responses to the “Trauma” of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, qualitative findings explicate how internal and external factors foster PTG, detailing the process of its formation. This consistency and complementarity between qualitative and quantitative approaches highlight the importance and value of employing a combined methodological perspective for a holistic understanding of PTG.